Director: Bernardo Bertolucci

MPAA rating: R, NC-17

Awards: New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actor, More

Screenplay: Bernardo Bertolucci, Franco Arcalli, Agnès Varda

Last Tango in Paris is a 1972 Franco-Italian erotic drama film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci which portrays a recently widowed American who begins an anonymous sexual relationship with a young Parisian woman.

Last Tango in Paris: Uncut Version Blu-ray Review

Bertolucci’s 1973 classic, Last Tango in Paris, starring Brando (he only needs one name), is infamous for its well known “butter” scene, so much so that people who know little else about the film think it is a rampant piece of erotica, no more than soft porn. In fact, Last Tango, burdened with a perplexing NC-17 rating in this release, is far more than that. It’s art, jazz, melodrama, and, yes, sex, all rolled into the superb cinematography of Vittotio Storaro.

Paul (Brando), distraught from his estranged wife’s recent, bloody suicide returns to France for her funeral where he meets Jeanne (the recently deceased Maria Schneider), a young, 20-year-old French girl in a complicated relationship with a filmmaker. The two soon take up a secret sexual relationship in a bare apartment, keeping their names from each other. Two lost souls, looking for an escape from the world and themselves. A tango of hot sex and hot emotional drama, set to the seething and sultry jazz of Gato Barbieri.

This is a classic European art house Drama – melodramatic, emotional, sensual, not always immediately apparent in its purpose, but always beautiful, and somehow perfectly capturing a real slice of life.

REVIEW BY ROGER EBERT

Bernardo Bertolucci's "Last Tango in Paris" is one of the great emotional experiences of our time. It's a movie that exists so resolutely on the level of emotion, indeed, that possibly only Marlon Brando, of all living actors, could have played its lead. Who else can act so brutally and imply such vulnerability and need?

For the movie is about need; about the terrible hunger that its hero, Paul, feels for the touch of another human heart. He is a man whose whole existence has been reduced to a cry for help -- and who has been so damaged by life that he can only express that cry in acts of crude sexuality.

Bertolucci begins with a story so simple (which is to say, so stripped of any clutter of plot) that there is little room in it for anything but the emotional crisis of his hero. The events that take place in the everyday world are remote to Paul, whose attention is absorbed by the gradual breaking of his heart. The girl, Jeanne, is not a friend and is hardly even a companion; it's just that because she happens to wander into his life, he uses her as an object of his grief.

The movie begins when Jeanne, who is about to be married, goes apartment-hunting and finds Paul in one of the apartments. It is a big, empty apartment, with a lot of sunlight but curiously little cheer. Paul rapes her, if rape is not too strong a word to describe an act so casually accepted by the girl. He tells her that they will continue to meet there, in the empty apartment, and she agrees.

Why does she agree? From her point of view -- which is not a terribly perceptive one -- why not? One of the several things this movie is about is how one person, who may be uncommitted and indifferent, nevertheless can at a certain moment become of great importance to another. One of the movie's strengths comes from the tragic imbalance between Paul's need and Jeanne's almost unthinking participation in it. Their difference is so great that it creates tremendous dramatic tension; more, indeed, than if both characters were filled with passion.

They do continue to meet, and at Paul's insistence they do not exchange names. What has come together in the apartment is almost an elemental force, not a connection of two beings with identities in society. Still, inevitably, the man and the girl do begin to learn about each other. What began, on the man's part, as totally depersonalized sex develops into a deeper relationship almost to spite him.

We learn about them. He is an American, living in Paris these last several years with a French wife who owned a hotel that is not quite a whorehouse. On the day the movie begins, the wife has committed suicide. We are never quite sure why, although by the time the movie is over we have a few depressing clues.

The girl is young, conscious of her beauty and the developing powers of her body, and is going to marry a young and fairly inane filmmaker. He is making a movie of their life together; a camera crew follows them around as he talks to her and kisses her -- for herself or for the movie, she wonders.

The banality of her "real" life has thus set her up for the urgency of the completely artificial experience that has been commanded for her by Paul. She doesn't know his name, or anything about him, but when he has sex with her it is certainly real; there is a life in that empty room that her fiance, with all of his cinema verite, is probably incapable of imagining.

She finds it difficult, too, because she is a child. A child, because she hasn't lived long enough and lost often enough to know yet what a heartbreaker the world can be. There are moments in the film when she does actually seem to look into Paul's soul and half-understand what she sees there, but she pulls back from it; pulls back, finally, all the way -- and just when he had come to the point where he was willing to let life have one more chance with him.

A lot has been said about the sex in the film; in fact, "Last Tango in Paris" has become notorious because of its sex. There is a lot of sex in this film -- more, probably, than in any other legitimate feature film ever made -- but the sex isn't the point, it's only the medium of exchange. Paul has somehow been so brutalized by life that there are only a few ways he can still feel.

Sex is one of them, but only if it is debased and depraved -- because he is so filled with guilt and self-hate that he chooses these most intimate of activities to hurt himself beyond all possibilities of mere thoughts and words. It is said in some quarters that the sex in the movie is debasing to the girl, but I don't think it is. She's almost a bystander, a witness at the scene of the accident. She hasn't suffered enough, experienced enough, to more than dimly guess at what Paul is doing to himself with her. But Paul knows, and so does Bertolucci; only an idiot would criticize this movie because the girl is so often naked but Paul never is.

That's their relationship.

The movie may not contain Brando's greatest performance, but it certainly contains his most emotionally overwhelming scene. He comes back to the hotel and confronts his wife's dead body, laid out in a casket, and he speaks to her with words of absolute hatred -- words which, as he says them, become one of the most moving speeches of love I can imagine.

As he weeps, as he attempts to remove her cosmetic death mask ("Look at you! You're a monument to your mother! You never wore makeup, never wore false eyelashes!"), he makes it absolutely clear why he is the best film actor of all time. He may be a bore, he may be a creep, he may act childish about the Academy Awards -- but there is no one else who could have played that scene flat-out, no holds barred, the way he did, and make it work triumphantly.

The girl, Maria Schneider, doesn't seem to act her role so much as to exude it. On the basis of this movie, indeed, it's impossible to really say whether she can act or not. That's not her fault; Bertolucci directs her that way. He wants a character who ultimately does not quite understand the situation she finds herself in; she has to be that way, among other reasons, because the movie's ending absolutely depends on it. What happens to Paul at the end must seem, in some fundamental way, ridiculous. What the girl does at the end has to seem incomprehensible -- not to us; to her.

What is the movie about? What does it all mean? It is about, and means, exactly the same things that Bergman's "Cries and Whispers" was about, and meant. That's to say that no amount of analysis can extract from either film a rational message. The whole point of both films is that there is a land in the human soul that's beyond the rational -- beyond, even, words to describe it.

Faced with a passage across that land, men make various kinds of accommodations. Some ignore it; some try to avoid it through temporary distractions; some are lucky enough to have the inner resources for a successful journey. But of those who do not, some turn to the most highly charged resources of the body; lacking the mental strength to face crisis and death, they turn on the sexual mechanism, which can at least be depended upon to function, usually.

That's what the sex is about in this film (and in "Cries and Whispers"). It's not sex at all (and it's a million miles from intercourse). It's just a physical function of the soul's desperation. Paul in "Last Tango in Paris" has no difficulty in achieving an erection, but the gravest difficulty in achieving a life-affirming reason for one.

Footnote, 1995

Watching Bernardo Bertolucci's "Last Tango in Paris" 23 years after it was first released is like revisiting the house where you used to live, and did wild things you don't do anymore. Wandering through the empty rooms, which are smaller than you remember them, you recall a time when you felt the whole world was right there in your reach, and all you had to do was take it.

This movie was the banner for a revolution that never happened. "The movie breakthrough has finally come," Pauline Kael wrote, in the most famous movie review ever published. "Bertolucci and Brando have altered the face of an art form." The date of the premiere, she said, would become a landmark in movie history comparable to the night in 1913 when Stravinsky's "The Rite of Spring" was first performed, and ushered in modern music.

"Last Tango" premiered, in case you have forgotten, on Oct. 14, 1972. It did not quite become a landmark. It was not the beginning of something new, but the triumph of something old -- the "art film," which was soon to be replaced by the complete victory of mass-marketed "event films." The shocking sexual energy of "Last Tango in Paris" and the daring of Marlon Brando and the unknown Maria Schneider did not lead to an adult art cinema. The movie frightened off imitators, and instead of being the first of many X-rated films dealing honestly with sexuality, it became almost the last. Hollywood made a quick U-turn into movies about teenagers, technology, action heroes and special effects. And with the exception of a few isolated films like "The Unbearable Lightness of Being" (1988) and "In the Realm of the Senses" (1976), the serious use of graphic sexuality all but disappeared from the screen.

I went to see "Last Tango in Paris" again because it is being revived at Facets Multimedia, that temple of great cinema, where the largest specialized video sales operation in the world subsidizes a little theater where people still gather to see great film projected through celluloid onto a screen. (I am reminded of the readers in Truffaut's "Fahrenheit 451" (1967), who committed books to memory in order to save them.)

It was a good 35 mm print, and I was drawn once again into the hermetic world of these two people, Paul and Jeanne, their names unknown to each other, who meet by chance in an empty Paris apartment and make sudden, brutal, lonely sex. Paul's marriage has just ended with his wife's suicide. Jeanne's marriage is a week or two away, and will supply the conclusion for a film being made by her half-witted fiancee.

In anonymous sex they find something that apparently they both need, and Bertolucci shows us enough of their lives to guess why. Paul (Brando) wants to bury his sense of hurt and betrayal in mindless animal passion. And Jeanne (Schneider) responds to the authenticity of his emotion, however painful, because it is an antidote to the prattle of her insipid boyfriend and bourgeoise mother. Obviously their "relationship," if that's what it is, cannot exist outside these walls, in the light of the real world.

The first time I saw the film there was the shock of its daring. The "butter scene" had not yet been cheapened in a million jokes, and Brando's anguished monologue over the dead body of his wife -- perhaps the best acting he has ever done -- had not been analyzed into pieces. It simply happened. I once had a professor who knew just about everything there was to know about Romeo and Juliet, and told us he would trade it all in for the opportunity to read the play for the first time. I felt the same way during the screening: I was so familiar with the film that I was making contact with the art instead of the emotion.

The look, feel and sound of the film are evocative. The music by Gato Barbieri is sometimes counterpoint, sometimes lament, but it is never simply used to tell us how to feel. Vittorio Storaro's slow tracking shots in the apartment, across walls and the landscapes of bodies, are cold and remote; there is no attempt to heighten the emotions. The sex is joyless and efficient, and beside the point: Whatever the reasons these two people have for what they do with one another, sensual pleasure is not one of them.

Brando, who can be the most mannered of actors, is here often affectless. He talks, he observes, he states things. He allows himself bursts of anger and that remarkable outpouring of grief, and then at the end he is wonderful in the way he lets all of the air out of Paul's character by turning commonplace with the speech where he says he likes her. The moment is wonderful because it releases the tension, it shows what was happening in that apartment, and we can feel the difference when it stops.

In my notes I wrote: "He is in scenes as an actor, she is in scenes as a thing." This is unfair. Maria Schneider, an unknown whose career dissipated after this film, does what she can with the role, but neither Brando nor Bertolucci was nearly as interested in Jeanne as in Paul. Because I was young in 1972, I was unable to see how young Jeanne (or Schneider) really was; the screenplay says she is 20 and Paul is 45, but now when I see the film she seems even younger, her open-faced lack of experience contradicting her incongrously full breasts. Both characters are enigmas, but Brando knows Paul, while Schneider is only walking in Jeanne's shoes.

The ending. The scene in the tango hall is still haunting, still part of the whole movement of the third act of the film, in which Paul, having created a searing moment out of time, now throws it away in drunken banality. The following scenes, leading to the unexpected events in the apartment of Jeanne's mother, strike me as arbitrary and contrived. But still Brando finds a way to redeem them, carefully remembering to park his gum before the most important moment of his life.

Thời lượng: 136 phút

Năm phát hành: 1972

Nghệ sĩ: Marlon Brando Maria Schneider Maria Michi

Danh mục phim: Phim Tâm Lý

Đạo diễn: Bernardo Bertolucci

Nhà sản xuất: United Artists Les Productions Artistes Associés Produzioni Europee Associati (PEA)

Quốc gia sản xuất: Pháp, Ý

Last Tango In Paris là một trong những bộ phim tai tiếng nhất thế kỷ 20, với cảnh sex bị đánh giá là đồi bại và có tính khiêu dâm. Phim đã bị cấm ở nhiều nước, cả ở một số vùng của Anh, dù được coi là tác phẩm số một của Bernardo Bertolucci và giành 3 đề cử Oscar (cho đạo diễn và 2 diễn viên chính). Maria Schneider nói: "Tôi đã xem lại Last Tango 3 năm trước, khi Marlon qua đời và thấy phim này chẳng có giá trị gì. Có lẽ Bertolucci đã được đánh giá quá cao. Sau bộ phim này, ông ấy chẳng làm được phim nào ra hồn nữa".

Maria Schneider - nữ diễn viên 19 tuổi khi đóng phim "Last Tango In Paris" (1972) - kể, cô cảm thấy mình bị Marlon xâm phạm khi đóng cảnh ân ái với ông.

Maria Schneider năm nay 55 tuổi, đang sống tại Paris. Cô nhớ lại: "Marlon Brando rất xấu hổ về cơ thể mình khi khỏa thân, còn tôi thì không thấy có vấn đề gì vì khi đó tôi còn trẻ. Sau phim này, tôi không bao giờ nhận lời đóng cảnh nude nữa dù có rất nhiều lời chào mời. Bây giờ khán giả đã quen với cảnh "hot" trên phim, nhưng phim của tôi và Marlon đã gây ra một trận cuồng phong khi phát hành năm 1972".

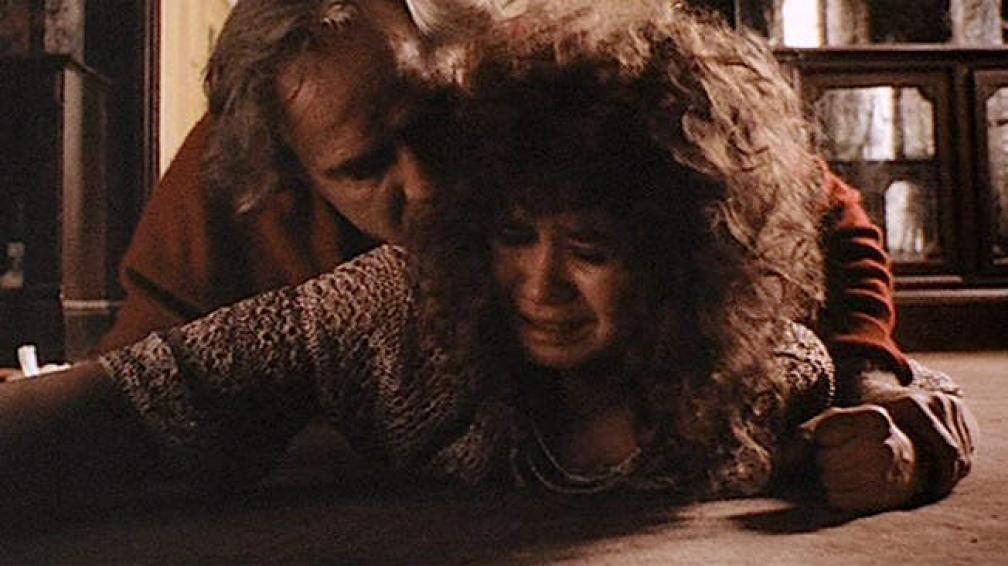

Maria cho biết, đoạn phim cô nằm trên sàn nhà với "bố già" không hề có trong kịch bản, mà là ý thích nhất thời của nam tài tử khi đó 48 tuổi. Cô rất giận dữ nhưng không biết phải làm sao.

Nữ diễn viên người Pháp nói: "Khi đó, tôi không hề biết rằng mình có quyền gọi cho công ty, luật sư và các nhà làm phim không được phép ép tôi đóng cảnh không có trong kịch bản. Marlon bảo tôi rằng, đó chỉ là làm phim thôi. Dù biết anh ấy không làm thật, nhưng tôi đã khóc. Tôi cảm thấy bị sỉ nhục, và - theo một nghĩa nào đó - bị cả Marlon và đạo diễn Bertolucci hiếp. Sau khi quay xong, bạn diễn của tôi không có một lời an ủi hay xin lỗi tôi. Ơn giời, chúng tôi chỉ quay một lần là đạt".

Câu chuyện về "Last Tango in Paris": Ranh giới mỏng manh giữa nghệ thuật và đạo đức

Việc đạo diễn Bernardo Bertolucci thừa nhận cảnh hiếp dâm trong bộ phim Last Tango in Paris là thật là tiêu điểm lớn gây chấn động thế giới điện ảnh tuần qua.

Last Tango in Paris là một bộ phim tình cảm được hợp tác sản xuất giữa hai nước Pháp – Ý. Phim chứa đựng những cảnh quay nhạy cảm về tình dục tới nỗi từng bị cấm chiếu ở nhiều quốc gia, bị cắt xén khi phát hành và được phân loại ở mức cao nhất, R hoặc NC-17. Nội dung phim xoay quanh mối quan hệ đầy nhục dục giữa một doanh nhân trung niên người Mỹ và một thiếu nữ Pháp xinh đẹp.

Dù bị chỉ trích hay đánh giá trái chiều, nhưng Last Tango in Paris vẫn được xem là một trong những tác phẩm tiêu biểu của điện ảnh thế kỷ XX. Nó đã mang lại hai đề cử Oscar Marlon Brando và Bernardo Bertolucci. Nhưng giờ đây, sau 44 năm, người ta mới biết được sự thật tồi tệ mà cả hai đã sắp đặt để mưu lợi cho mình.

Cảnh phim nhạy cảm và ám ảnh nhất chính là khi nhân vật nữ do Maria Schneider thủ vai bị nam chính Marlon Brando tấn công tình dục. Một cảnh phim đầy đau đớn và buồn thảm khi nhân vật của Marlon cưỡng bức cô gái mà hắn yêu trong sự tuyệt vọng. Cái cảm giác sợ hãi, hốt hoảng của Maria khiến cho tất cả trở nên thật tới không ngờ. Và nó đúng thật không phải chỉ là diễn.

Để thu được hiệu ứng chân thật, Marlon đã sử dụng một "cây gậy bơ" đụng chạm vào người Maria mà không hề báo cho cô biết trước

Bernardo nói rằng để tạo cảm giác thật, ông cùng Marlon đã nảy ra ý tưởng sử dụng "thanh bơ" cho cảnh quay. Mặc dù nữ diễn viên Maria Schneider biết rằng sẽ thực hiện cảnh quay cưỡng bức nhưng riêng chi tiết về "thanh gậy bơ" thì không. Lý giải cho hành động không báo trước với Maria, Bernardo Bertolucci chẳng ngần ngại tiết lộ vì ông ta muốn "phản ứng thật của một cô gái chứ không phải của một diễn viên". Năm đó, Maria chỉ vừa tròn 19 tuổi với cơ hội diễn xuất trong bộ phim đầu tay. Còn Bradon đã là một trung niên 48 tuổi dày dặn tuổi đời và tuổi nghề.

Trong khi Marlon Brandon và Bernardo Bertolucci được vinh danh và ca tụng. Thì nữ diễn viên Pháp Maria Schneider lại bị nhấn chìm trong khủng hoảng, cả trong công việc lẫn cuộc sống. Maria đã từng nói, quay bộ phim này là sự hối hận duy nhất của bà. Vì nó đã phá hủy hoàn toàn cuộc sống của bà.

Maria đã mất vào năm 2011 ở tuổi 58. Trong suốt cuộc đời mình, bà đã tham gia gần 50 bộ phim lớn nhỏ. Nhưng những gì mà người ta nhớ đến Maria Schneider vẫn chỉ là cô gái Paris xinh đẹp nhỏ nhắn trong Last Tango in Paris. Những cảnh quay sex trong phim đã biến Maria trở thành một biểu tượng nhục dục và khép lại cơ hội được đóng những phim nghiêm túc của một diễn viên trẻ mới vào nghề.

Không chỉ bị "đóng khung" trên màn ảnh, những ám ảnh của vụ tấn công tình dục công khai ấy còn khiến Maria trở nên trầm cảm và suy sụp. Sau Last Tango in Paris, bà đã gặp rất nhiều bất ổn trong tâm lý rồi rơi vào tình trạng nghiện thuốc. Thậm chí, là cả những nỗ lực để tự sát. Maria không bao giờ đóng cảnh khỏa thân một lần nào nữa.

"Họ chỉ báo cho tôi biết sau khi đã quay cảnh đó xong và tôi đã rất tức giận. Đáng lý tôi phải gọi cho đại diện để kiện họ vì đã bắt tôi làm điều không có trong kịch bản. Nhưng lúc đó, tôi không hề biết điều đó. Marlon nói với tôi rằng: "Đừng lo, chỉ là phim thôi mà", nhưng suốt cảnh quay ấy, những gì Marlon làm khiến tôi phải òa khóc. Tôi cảm giác như mình đã bị cả Marlon và Bertolucci cưỡng bức. Sau khi quay xong, Marlon còn chẳng đếm xỉa hay xin lỗi tôi một lời. Điều an ủi là may sao, nó chỉ quay đúng một lần".

Năm 2007, Maria đã chính thức lên tiếng về sự thật đằng sau cảnh quay năm xưa trên tờ Daily Mail. Nhưng đáp lại lời tố cáo, nhiều kẻ đã nói rằng Maria chỉ là một diễn viên vô danh đang muốn gây sự chú ý.

Tại sao khi Maria Schneider lên tiếng, sự việc chẳng gây một chú ý nào đáng kể. Nhưng khi Bernardo Bertolucci công khai thừa nhận. Thì chúng ta lại bùng nổ vì tức giận? Là vì sự lan tỏa thông tin của ngày ấy không giống như bây giờ? Hay căn bản là vì lời nói của Maria thì không đáng tin bằng lời của Bernardo?

Có bao nhiêu người dám thừa nhận những gì họ đã làm? Thật ra Bernardo đã cảm thấy đủ an toàn để nói ra những điều này trên truyền hình, trong bối cảnh chúng ta đang sống: một nền văn hóa bảo vệ cho những kẻ hiếp dâm. Nơi mà nạn nhân dễ dàng bị tấn công bằng đủ mọi hình thức và thủ phạm, chủ yếu là nam giới vẫn có thể nhởn nhơ. Điều mà Bernardo không lường trước, chính là tính hai chiều của truyền thông ngày nay.

Chỉ là một cây gậy bơ thì chẳng phải là hiếp dâm – nhiều khán giả nam giới đã đáp trả sự tức giận dành cho Bernardo và Marlon

Nhiều người lên tiếng lập luận: nó không phải là "hiếp dâm" vì làm gì có quan hệ tình dục thật sự giữa hai diễn viên. Cây gậy bơ chỉ là đạo cụ và vật tiếp xúc duy nhất vào nơi nhạy cảm. Vậy thì cảm xúc của một người phụ nữ khi bất ngờ bị tấn công là không đáng quan tâm ư? Vậy thì nếu bạn băn khoăn tại sao các nạn nhân bị lạm dụng không dám đứng lên vạch trần tội ác, thì bạn đã có câu trả lời rồi đấy.

Nhưng điều đó chẳng đáng sợ bằng việc: chúng ta - công chúng xem phim vẫn điềm nhiên bỏ qua tất cả tai tiếng của những ngôi sao đạo diễn, diễn viên ấy chỉ vì họ đã làm ra những bộ phim tuyệt vời. Thay vì dành thời gian xem xét những lời tố cáo vây quanh họ, thì họ chỉ đơn giản phớt lờ và đưa ra kết luận: "Tất cả là vì nghệ thuật" hay "Ranh giới giữa nghệ thuật và đạo đức đôi khi mỏng manh lắm".

Vẫn biết, nghệ thuật là đòi hỏi sự hy sinh. Nhưng những thứ được đánh đổi bằng nhân tính và đạo đức thì có được coi là nghệ thuật chân chính hay không?

No comments:

Post a Comment